REVIEW BY JAMES CROSSLEY

Island Books (Mercer Island, WA)

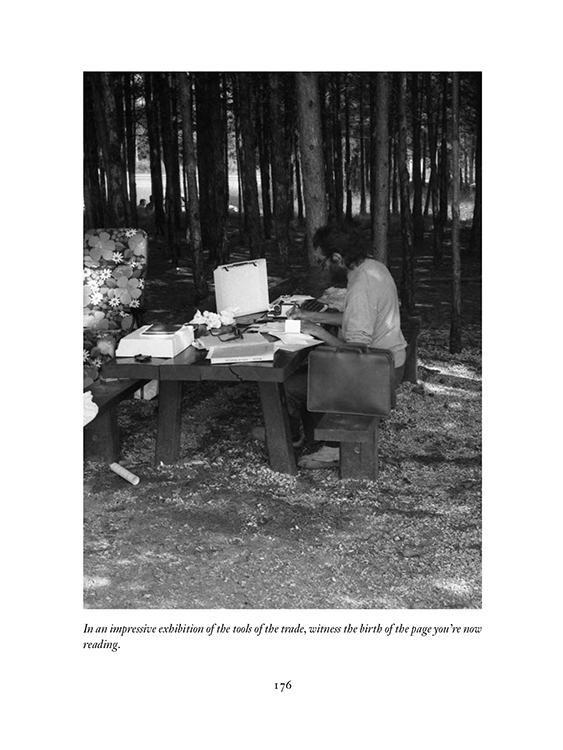

In 1982 Julio Cortázar and his wife Carol Dunlop embarked on an expedition that they first envisioned four years before when their relationship was new. After considerable planning, preparation of provisions, and the painstaking packing of their red VW camper van, they left Paris on L'autoroute du Sud heading for Marseille. What for most would be an eight-hour drive took them just over a month. During that time they never once left the highway: each day they broke for lunch at the first rest stop they encountered, fastidiously documented the flora, fauna, and human activity they discovered there, and then continued to the next, where they dined and repeated their pseudo-scientific procedures before calling it a night. Inch by inch they made their way toward the Mediterranean coast, exploring with mock gravity their responses to the landscape (what little could be seen of it from the verges of the road), to their art (practiced daily on portable typewriters), and to each other. The diary they left of this journey is charming, ridiculous, and more substantive than anyone has a right to expect.

In it, Dunlop describes the pair as "[c]osmonauts of the autoroute, like interplanetary travellers who observe from afar the rapid aging of those who remain subject to the laws of terrestrial time," and asks, "what are we going to discover when we go at camel speed after so many trips in airplanes, subways, trains?" Cortázar clarifies that this is really a journey to the interior, a self-examination: “Autonauts of the Cosmoroute ... The other path." Theirs is not an indulgent, solipsistic book, however. Even as the world passes by them in a blur, they remain engaged with it, commenting on the issues of the day, including the war in the Falkland Islands. They also engage with the audience that they expect will follow the traces they leave behind, expressing "hope, oh patient companion of these pages, that our experience has opened some doors for you too, and that some parallel freeway project of your own invention is already germinating."

The pen-and-ink illustrations of their campsites, done by Dunlop's son (then a teenager), accentuate the fanciful aspects of the project, but it's their own photography that actually connects to the text. Philosophical discursions are often undercut by intentionally banal shots of open asphalt and souvenir stands, and seemingly insignificant vacation snaps are frequently elevated by apposite captioning, ensuring a consistently amusing tone. It's as a portrait of a partnership that the imagery is most valuable, though. Two pictures by themselves, the first of the famously tall Cortázar looming over the roof of the van and the second of the petite Dunlop standing on the bumper, bring the couple to life in a way that prose alone never could, and there are dozens more like them in Autonauts. They form a candid, permanent record of a few fleeting weeks when two people tried to slow the calendar down.

Within months after the journey ended, Dunlop had succumbed to illness and died at the age of 36. Cortázar had time to eulogize her in a final chapter, written before the book was published in 1983. It was the final work he produced before he too died the following year.

Autonauts of the Cosmoroute is translated from the Spanish by Anne McLean, published by Archipelago Books and distributed by Penguin Random House.

$20 PB 354 pages with 164 bw illustrations ISBN: 978-0-9793330-0-2 Pub date: November 2007