In his review of Rikki Ducornet's The Deep Zoo, bookseller and writer Stephen Sparks asks, "Do we want art to lull us or arouse us?" He lauds Ducornet for "pushing against the limits, both formal and moral, imposed upon the imagination by those who fear the consequences of ingenuity and freedom." Ducornet's book, along with the other four titles reviewed here (by booksellers from some of the best indie bookstores in the country—Elliott Bay Book Company, Green Apple Books, Greenlight Bookstore, and Odyssey Bookshop) not only resist that fear but also subvert the powers that wield it.

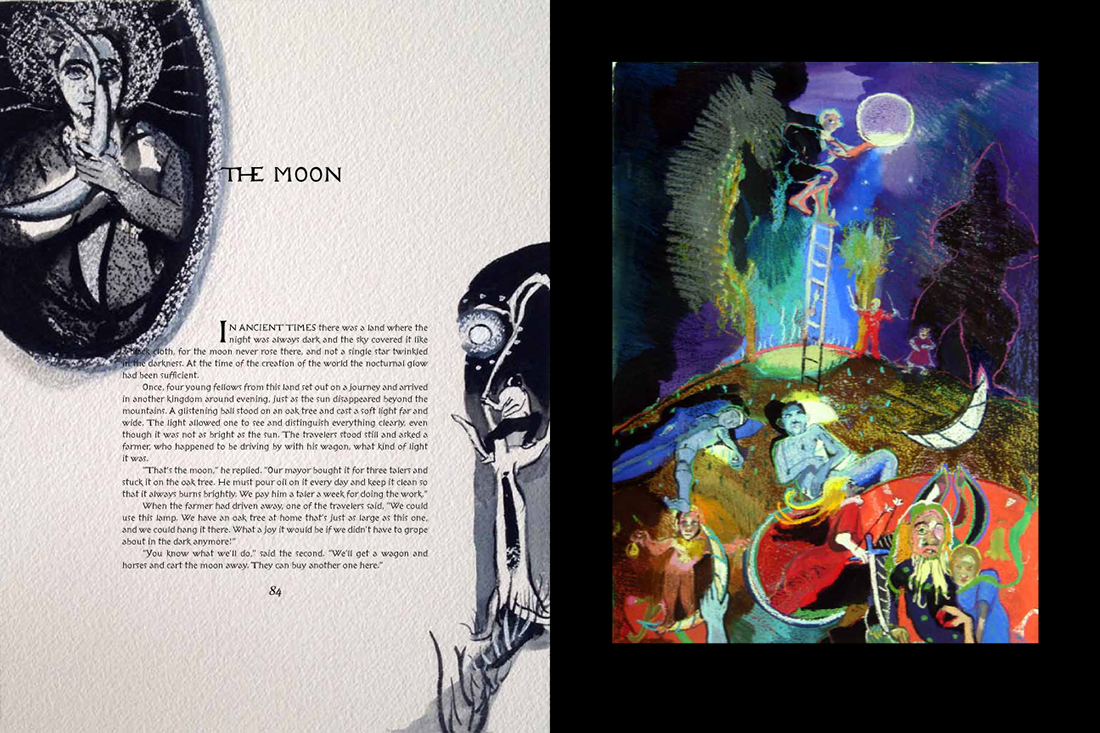

There was some design to this issue's selection of titles (while there hasn't been in previous issues). The Improbable, No. 5 is timed to release just before Book Expo America, the largest book trade event in North America: a vast landscape of the book as an algorithm-friendly commodity, easily digestible, trend-compliant, the safest bet. These five books, in contrast, are exquisitely category-resistant, embracing real risk-taking and the multiplicitous natures of reality, preferring juxtaposition and synthesis over the literal and the linear, and thus they inhabit a very different terrain, one that The Improbable seeks to illuminate.

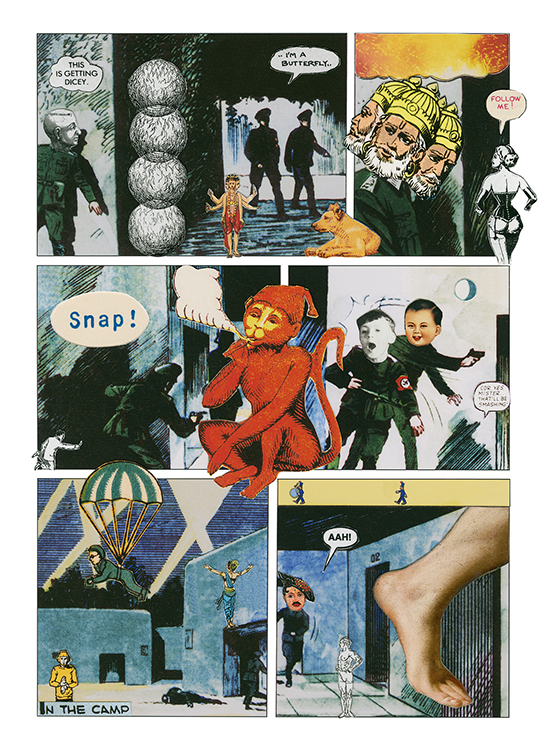

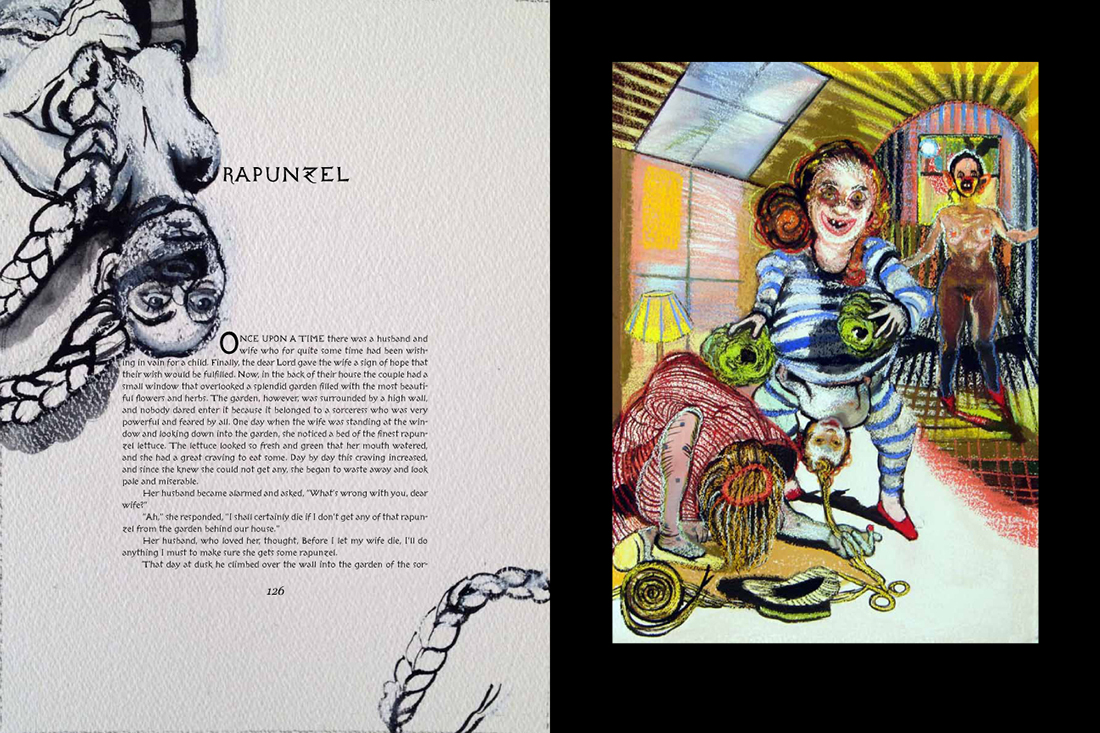

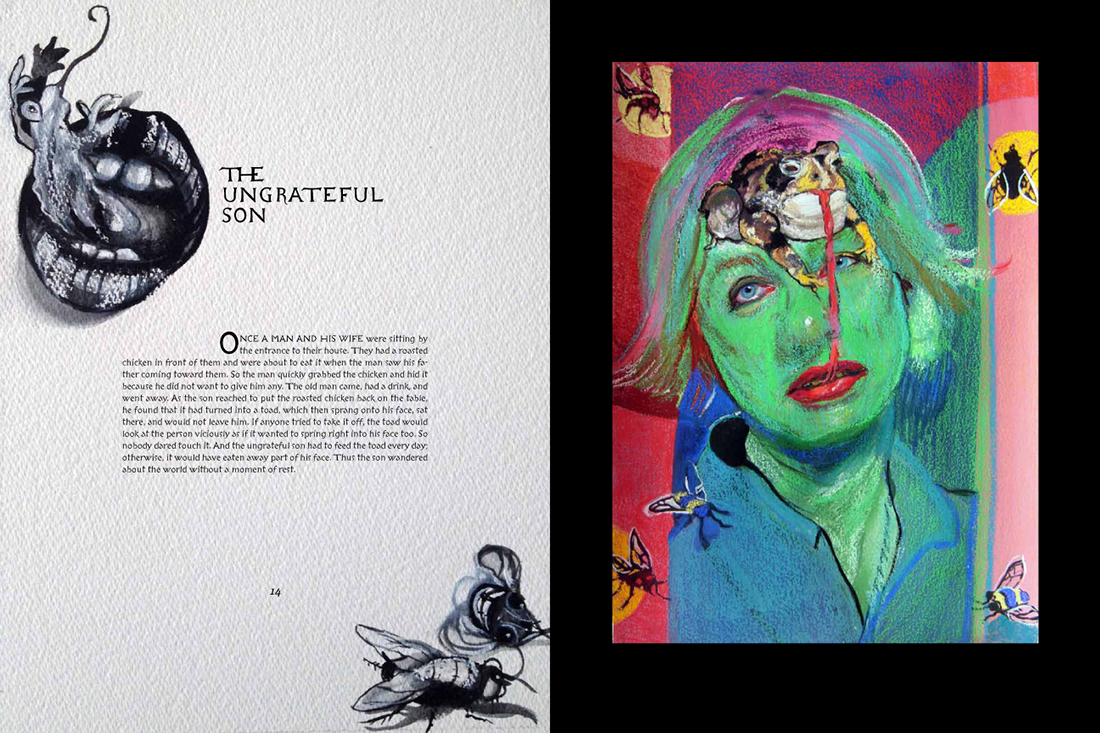

Ryan Mihaly in his review of Here Comes Kitty: A Comic Opera describes the book like this: "what is often split into binaries are together at play: order and chaos, reality and dream, sense and nonsense." I think that's applicable to the other books included here as well, and I find it very interesting that all of books here also have a direct or implicit reference to animals, pointing directly to those other binaries—animal and human, wilderness and culture, instinct and rationality. They also invoke the "creatureness" in every reader—senses electrified, awareness sharpened to see the unfamiliar in the familiar landscape (and vice-versa), intelligence and emotion intertwined rather than at odds. Finally, in all these ways, these five books (the artists and writers who've authored them and the publishers who have published them) are challenging the very powers that tell us what kind of books we want to read.

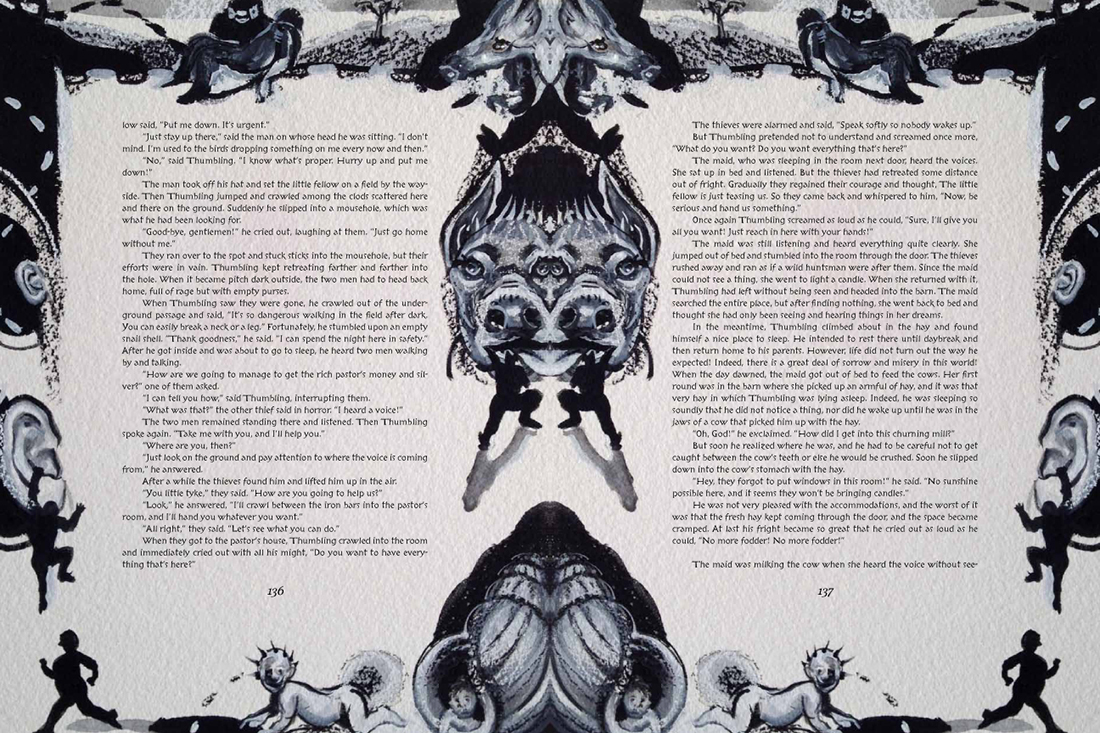

The Improbable is all about hybridity. In this issue, the books are truly chimerical. If it's your first time here, I hope you'll look through other issues to see all the fantastic species that occupy a richly diverse world of books beyond the manicured lawns and gridded streets.

—Lisa Pearson, editor

p.s. Look for the next issue of The Improbable later in summer as we're taking a month (or two!) off. Sign up for our mailing list to make sure you get the announcement, or follow us @thehybridbook on Twitter. And if you like a review or a book, please help us spread the word!