REVIEW BY JARROD ANNIS

Greenlight Bookstore (Brooklyn)

Erik Satie never really had a time of his own. He sat perfectly astride the Belle Époque and the Modern era, though he never belonged to either, which imbues his work with a particular sense of timelessness. A proto-minimalist and spiritual godfather to ambient music, it wasn’t until John Cage elevated Satie to the level of near-sainthood in the mid 20th century that his work became more widely known. Atlas’s sexy hardcover edition of A Mammal’s Notebook is the most extensive collection of Satie’s writings to appear in English, from annotations to his musical scores, published articles and the contents of his private notebooks. To read A Mammal’s Notebook is to be lead through the looking-glass mirror museum of Satie’s mind by a pied piper playing Dada sonatas. Even when viewed apart from his music, A Mammal’s Notebook provides a unique vantage point into the mind of an iconoclastic kook and visionary oddball.

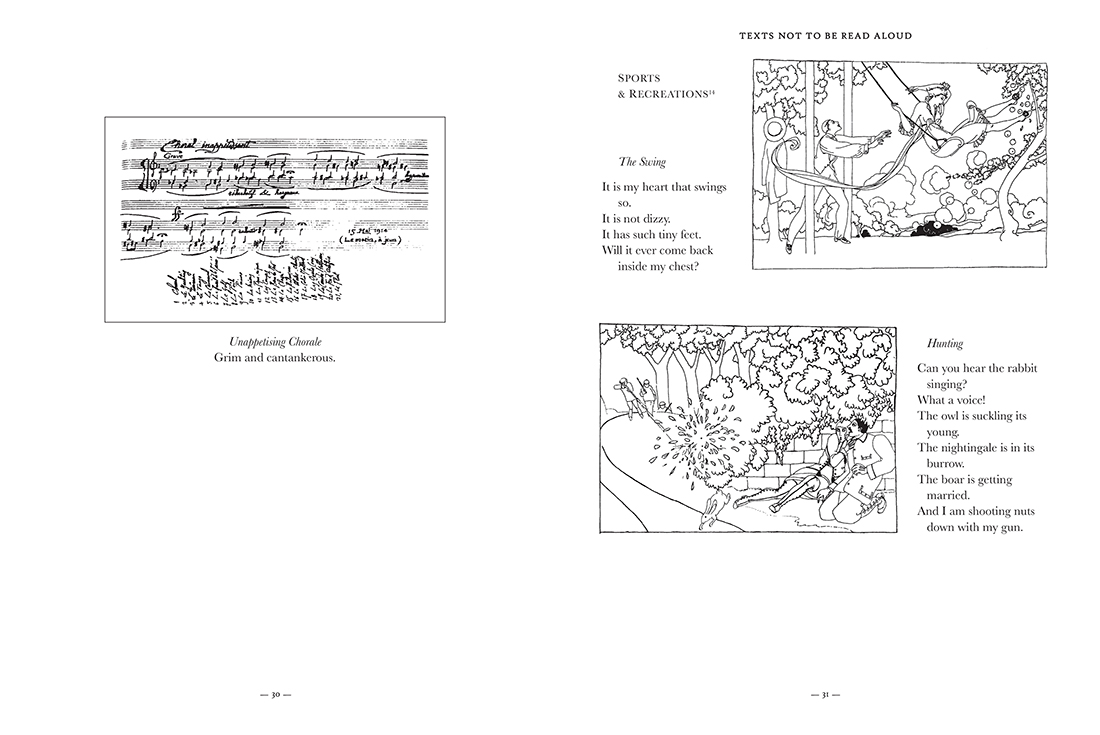

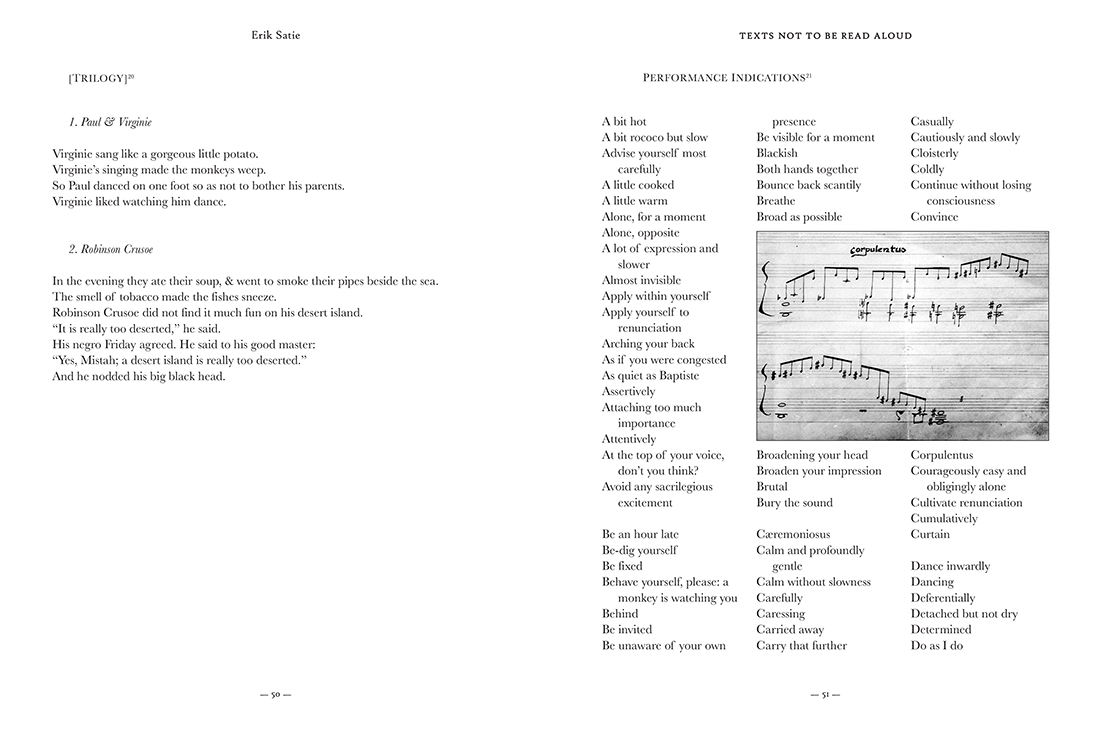

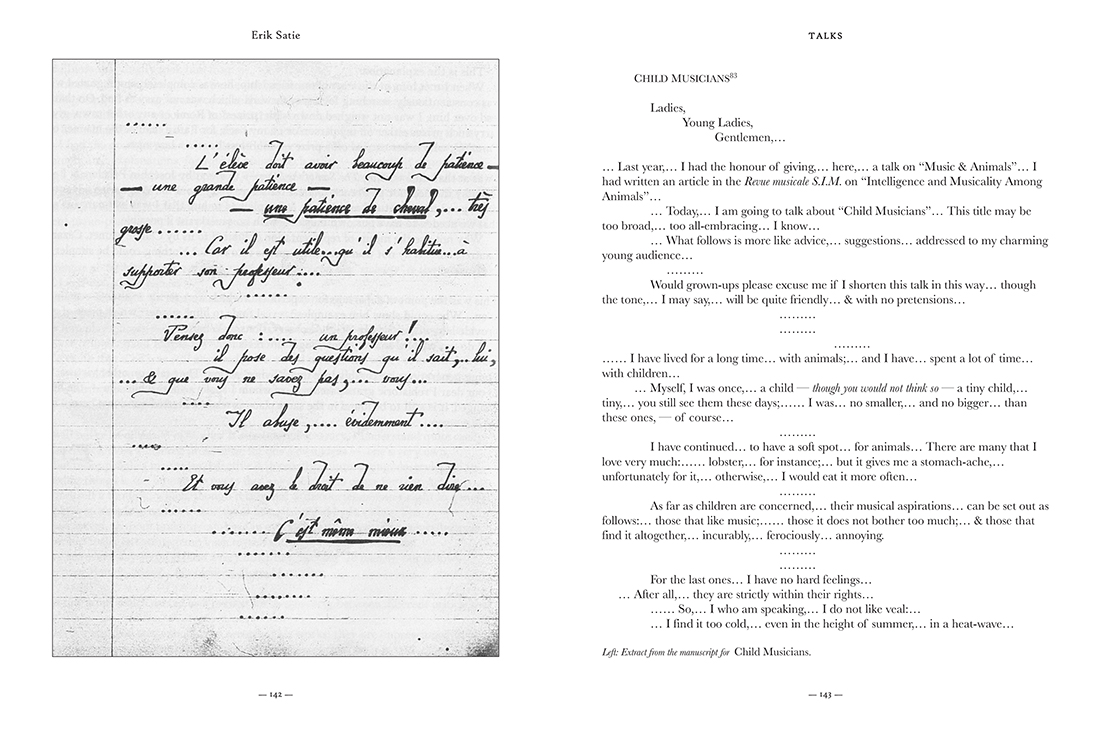

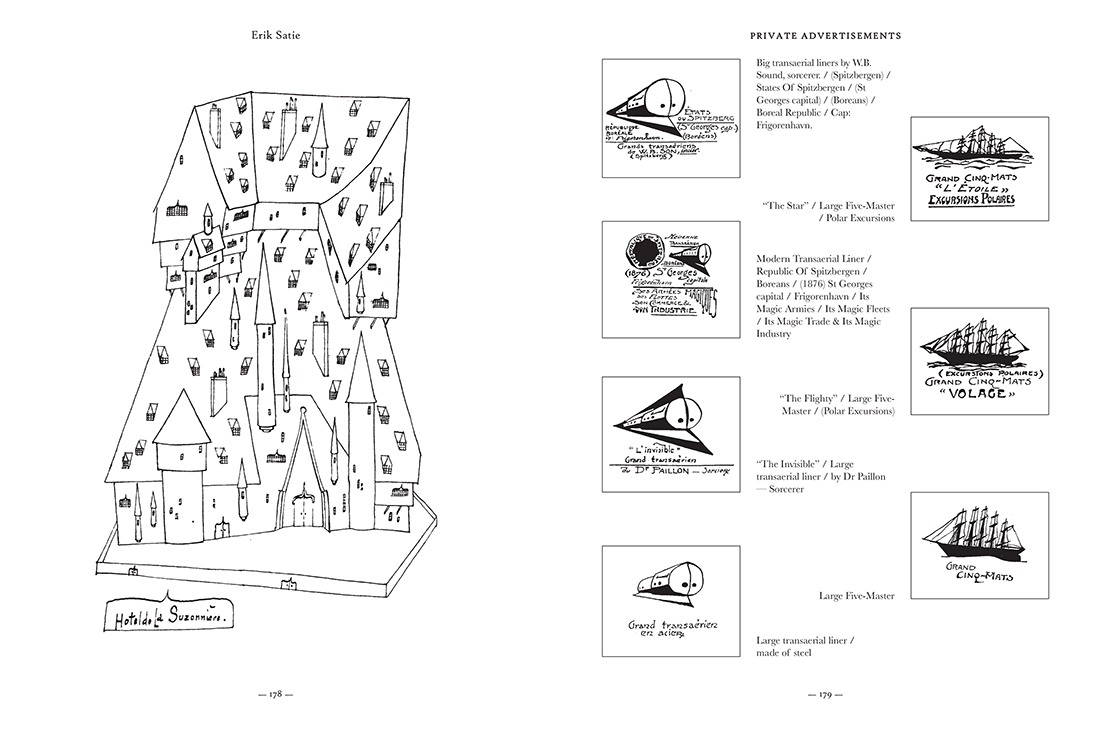

The texts collected in A Mammal’s Notebook aren’t mere musing on art and craft. They serve more as blueprints for the looking-glass world that Satie created around himself, not out of isolation, but because it seemed a more interesting place to be. Many of the entries here could be viewed in relation to the nonsense writing of Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear, or Christian Morgenstern, but Satie’s is a distinctly applied nonsense—with heavy overtones of Dada and absurdism. Indeed, Satie was an absurdist par-excellence, but never for mere amusement. His absurdity served as the ethos that he applied to every aspect of his life and work. From his musical annotations to his beautiful calligraphic drawings and “advertisements” for fictional establishment, it becomes increasingly clear that Satie’s reality may have been more of a subjective experience in its nature. Satie wasn’t out to replace reality; he just subverted the one that was already in place. One of the more interesting entries relating to his musical career is a glossary of Satie’s own “Performance Indications,” used in lieu of standard dynamics to annotate his scores. Satie might instruct a measure to be played “Dry as a cuckoo,” “Under the pomegranates,” or “With tears in your fingers.”

While much of Satie’s writing has to do with music and art, he’s never stodgy or academic. Like his music, Satie’s writing is calculated and deliberate, but always with a kind tongue firmly in cheek. He writes, “I started playing snatches of Music which I made up myself . . . All my troubles stem from this . . .” There’s always a self-awareness present that allows readers to put complete faith in Satie’s charmingly bizarre notions. If kneeling at the altar of benevolent prankster saints is your thing, A Mammal’s Notebook needs to be on your bookshelf.

A Mammal’s Notebook: The Writings of Erik Satie is published by Atlas Press and distributed by D.A.P./Artbook.com.

$35 HB 224 pages, 153 bw illustrations ISBN: 9781900565660 Pub date: July 31, 2014